|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

Western |

+ |

|

Vulpines |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

That's not what they meant... |

+ |

|

Graves, roofs, and your own living room |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

Where next? |

+ |

|

|

|

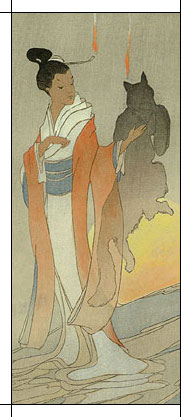

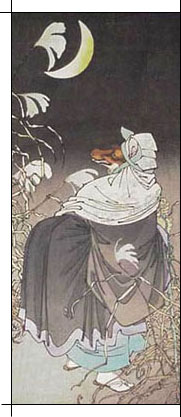

The Grateful FoxesOne fine spring day, two friends went out to a moor to gather fern, attended by a boy with a bottle of wine and a box of provisions. As they were straying about, they saw at the foot of a hill a fox that had brought out its cub to play; and whilst they looked on, struck by the strangeness of the sight, three children came up from a neighbouring village with baskets in their hands, on the same errand as themselves. As soon as the children saw the foxes, they picked up a bamboo stick and took the creatures stealthily in the rear; and when the old foxes took to flight, they surrounded them and beat them with the stick, so that they ran away as fast as their legs could carry them; but two of the boys held down the cub, and, seizing it by the scruff of the neck, went off in high glee. The two friends were looking on all the while, and one of them, raising his voice, shouted out, "Hallo! you boys! what are you doing with that fox?" The eldest of the boys replied, "We're going to take him home and sell him to a young man in our village. He'll buy him, and then he'll boil him in a pot and eat him." "Well," replied the other, after considering the matter attentively, "I suppose it's all the same to you whom you sell him to. You'd better let me have him." "Oh, but the young man from our village promised us a good round sum if we could find a fox, and got us to come out to the hills and catch one; and so we can't sell him to you at any price." "Well, I suppose it cannot be helped, then; but how much would the young man give you for the cub?" "Oh, he'll give us three hundred cash at least." "Then I'll give you half a bu;78 and so you'll gain five hundred cash by the transaction." "Oh, we'll sell him for that, sir. How shall we hand him over to you?" "Just tie him up here," said the other; and so he made fast the cub round the neck with the string of the napkin in which the luncheon-box was wrapped, and gave half a bu to the three boys, who ran away delighted. The man's friend, upon this, said to him, "Well, certainly you have got queer tastes. What on earth are you going to keep the fox for?" "How very unkind of you to speak of my tastes like that. If we had not interfered just now, the fox's cub would have lost its life. If we had not seen the affair, there would have been no help for it. How could I stand by and see life taken? It was but a little I spent—only half a bu—to save the cub, but had it cost a fortune I should not have grudged it. I thought you were intimate enough with me to know my heart; but to-day you have accused me of being eccentric, and I see how mistaken I have been in you. However, our friendship shall cease from this day forth." And when he had said this with a great deal of firmness, the other, retiring backwards and bowing with his hands on his knees, replied— "Indeed, indeed, I am filled with admiration at the goodness of your heart. When I hear you speak thus, I feel more than ever how great is the love I bear you. I thought that you might wish to use the cub as a sort of decoy to lead the old ones to you, that you might pray them to bring prosperity and virtue to your house. When I called you eccentric just now, I was but trying your heart, because I had some suspicions of you; and now I am truly ashamed of myself." And as he spoke, still bowing, the other replied, "Really! was that indeed your thought? Then I pray you to forgive me for my violent language." When the two friends had thus become reconciled, they examined the cub, and saw that it had a slight wound in its foot, and could not walk; and while they were thinking what they should do, they spied out the herb called "Doctor's Nakasé," which was just sprouting; so they rolled up a little of it in their fingers and applied it to the part. Then they pulled out some boiled rice from their luncheon-box and offered it to the cub, but it showed no sign of wanting to eat; so they stroked it gently on the back, and petted it; and as the pain of the wound seemed to have subsided, they were admiring the properties of the herb, when, opposite to them, they saw the old foxes sitting watching them by the side of some stacks of rice straw. "Look there! the old foxes have come back, out of fear for their cub's safety. Come, we will set it free!" And with these words they untied the string round the cub's neck, and turned its head towards the spot where the old foxes sat; and as the wounded foot was no longer painful, with one bound it dashed to its parents' side and licked them all over for joy, while they seemed to bow their thanks, looking towards the two friends. So, with peace in their hearts, the latter went off to another place, and, choosing a pretty spot, produced the wine bottle and ate their noon-day meal; and after a pleasant day, they returned to their homes, and became firmer friends than ever. Now the man who had rescued the fox's cub was a tradesman in good circumstances: he had three or four agents and two maid-servants, besides men-servants; and altogether he lived in a liberal manner. He was married, and this union had brought him one son, who had reached his tenth year, but had been attacked by a strange disease which defied all the physician's skill and drugs. At last a famous physician prescribed the liver taken from a live fox, which, as he said, would certainly effect a cure. If that were not forthcoming, the most expensive medicine in the world would not restore the boy to health. When the parents heard this, they were at their wits' end. However, they told the state of the case to a man who lived on the mountains. "Even though our child should die for it," they said, "we will not ourselves deprive other creatures of their lives; but you, who live among the hills, are sure to hear when your neighbours go out fox-hunting. We don't care what price we might have to pay for a fox's liver; pray, buy one for us at any expense." So they pressed him to exert himself on their behalf; and he, having promised faithfully to execute the commission, went his way. In the night of the following day there came a messenger, who announced himself as coming from the person who had undertaken to procure the fox's liver; so the master of the house went out to see him. "I have come from Mr. So-and-so. Last night the fox's liver that you required fell into his hands; so he sent me to bring it to you." With these words the messenger produced a small jar, adding, "In a few days he will let you know the price." When he had delivered his message, the master of the house was greatly pleased, and said, "Indeed, I am deeply grateful for this kindness, which will save my son's life." Then the goodwife came out, and received the jar with every mark of politeness. "We must make a present to the messenger." "Indeed, sir, I've already been paid for my trouble." "Well, at any rate, you must stop the night here." "Thank you, sir: I've a relation in the next village whom I have not seen for a long while, and I will pass the night with him;" and so he took his leave, and went away. The parents lost no time in sending to let the physician know that they had procured the fox's liver. The next day the doctor came and compounded a medicine for the patient, which at once produced a good effect, and there was no little joy in the household. As luck would have it, three days after this the man whom they had commissioned to buy the fox's liver came to the house; so the goodwife hurried out to meet him and welcome him. "How quickly you fulfilled our wishes, and how kind of you to send at once! The doctor prepared the medicine, and now our boy can get up and walk about the room; and it's all owing to your goodness." "Wait a bit!" cried the guest, who did not know what to make [pg 216] of the joy of the two parents. "The commission with which you entrusted me about the fox's liver turned out to be a matter of impossibility, so I came to-day to make my excuses; and now I really can't understand what you are so grateful to me for." "We are thanking you, sir," replied the master of the house, bowing with his hands on the ground, "for the fox's liver which we asked you to procure for us." "I really am perfectly unaware of having sent you a fox's liver: there must be some mistake here. Pray inquire carefully into the matter." "Well, this is very strange. Four nights ago, a man of some five or six and thirty years of age came with a verbal message from you, to the effect that you had sent him with a fox's liver, which you had just procured, and said that he would come and tell us the price another day. When we asked him to spend the night here, he answered that he would lodge with a relation in the next village, and went away." The visitor was more and more lost in amazement, and; leaning his head on one side in deep thought, confessed that he could make nothing of it. As for the husband and wife, they felt quite out of countenance at having thanked a man so warmly for favours of which he denied all knowledge; and so the visitor took his leave, and went home. That night there appeared at the pillow of the master of the house a woman of about one or two and thirty years of age, who said, "I am the fox that lives at such-and-such a mountain. Last spring, when I was taking out my cub to play, it was carried off by some boys, and only saved by your goodness. The desire to requite this kindness pierced me to the quick. At last, when calamity attacked your house, I thought that I might be of use to you. Your son's illness could not be cured without a liver taken from a live fox, so to repay your kindness I killed my cub and took out its liver; then its sire, disguising himself as a messenger, brought it to your house." And as she spoke, the fox shed tears; and the master of the house, wishing to thank her, moved in bed, upon which his wife awoke and asked him what was the matter; but he too, to her great astonishment, was biting the pillow and weeping bitterly. "Why are you weeping thus?" asked she. At last he sat up in bed, and said, "Last spring, when I was out on a pleasure excursion, I was the means of saving the life of a fox's cub, as I told you at the time. The other day I told Mr. So-and-so that, although my son were to die before my eyes, I would not be the means of killing a fox on purpose; but asked him, in case he heard of any hunter killing a fox, to buy it for me. How the foxes came to hear of this I don't know; but the foxes to whom I had shown kindness killed their own cub and took out the liver; and the old dog-fox, disguising himself as a messenger from the person to whom we had confided the commission, came here with it. His mate has just been at my pillow-side and told me all about it; hence it was that, in spite of myself, I was moved to tears." When she heard this, the goodwife likewise was blinded by her tears, and for a while they lay lost in thought; but at last, coming to themselves, they lighted the lamp on the shelf on which the family idol stood, and spent the night in reciting prayers and praises, and the next day they published the matter to the household and to their relations and friends. Now, although there are instances of men killing their own children to requite a favour, there is no other example of foxes having done such a thing; so the story became the talk of the whole country. Now, the boy who had recovered through the efficacy of this medicine selected the prettiest spot on the premises to erect a shrine to Inari Sama,79 the Fox God, and offered sacrifice to the two old foxes, for whom he purchased the highest rank at the court of the Mikado. The Author's NoteThe passage in the tale which speaks of rank being purchased for the foxes at the court of the Mikado is, of course, a piece of nonsense. "The saints who are worshipped in Japan," writes a native authority, "are men who, in the remote ages, when the country was developing itself, were sages, and by their great and virtuous deeds having earned the gratitude of future generations, received divine honours after their death. How can the Son of Heaven, who is the father and mother of his people, turn dealer in ranks and honours? If rank were a matter of barter, it would cease to be a reward to the virtuous." All matters connected with the shrines of the Shintô, or indigenous religion, are confided to the superintendence of the families of Yoshida and Fushimi, Kugés or nobles of the Mikado's court at Kiyôto. The affairs of the Buddhist or imported religion are under the care of the family of Kanjuji. As it is necessary that those who as priests perform the honourable office of serving the gods should be persons of some standing, a certain small rank is procured for them through the intervention of the representatives of the above noble families, who, on the issuing of the required patent, receive as their perquisite a fee, which, although insignificant in itself, is yet of importance to the poor Kugés, whose penniless condition forms a great contrast to the wealth of their inferiors in rank, the Daimios. I believe that this is the only case in which rank can be bought or sold in Japan. In China, on the contrary, in spite of what has been written by Meadows and other admirers of the examination system, a man can be what he pleases by paying for it; and the coveted button, which is nominally the reward of learning and ability, is more often the prize of wealthy ignorance. The saints who are alluded to above are the saints of the whole country, as distinct from those who for special deeds are locally worshipped. To this innumerable class frequent allusion is made in these Tales. Touching the remedy of the fox's liver, prescribed in the tale, I may add that there would be nothing strange in this to a person acquainted with the Chinese pharmacopoeia, which the Japanese long exclusively followed, although they are now successfully studying the art of healing as practised in the West. When I was at Peking, I saw a Chinese physician prescribe a decoction of three scorpions for a child struck down with fever; and on another occasion a groom of mine, suffering from dysentery, was treated with acupuncture of the tongue. The art of medicine would appear to be at the present time in China much in the state in which it existed in Europe in the sixteenth century, when the excretions and secretions of all manner of animals, saurians, and venomous snakes and insects, and even live bugs, were administered to patients. "Some physicians," says Matthiolus, "use the ashes of scorpions, burnt alive, for retention caused by either renal or vesical calculi. But I have myself thoroughly experienced the utility of an oil I make myself, whereof scorpions form a very large portion of the ingredients. If only the region of the heart and all the pulses of the body be anointed with it, it will free the patients from the effects of all kinds of poisons taken by the mouth, corrosive ones excepted." Decoctions of Egyptian mummies were much commended, and often prescribed with due academical solemnity; and the bones of the human skull, pulverized and administered with oil, were used as a specific in cases of renal calculus. (See Petri Andreæ Matthioli Opera, 1574.) These remarks were made to me by a medical gentleman to whom I

mentioned the Chinese doctor's prescription of scorpion tea, and

they seem to me so curious that I insert them for comparison's sake. This story appears in Tales of Old Japan, by Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford. It and its illustrations are available thanks to the efforts of Project Gutenberg, whose license states: This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with |