|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

Western |

+ |

|

Vulpines |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

That's not what they meant... |

+ |

|

Graves, roofs, and your own living room |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

Where next? |

+ |

|

|

|

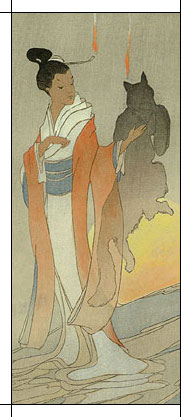

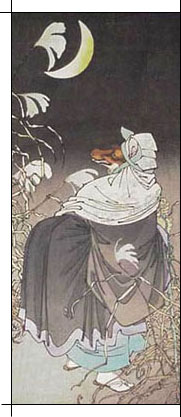

Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan: KitsuneLafcadio Hearn's accounts of his travels through Japan contain dozens of scattered references to kitsune, plus an entire chapter devoted to them. This is that chapter. If you would like to read the rest of the book, it's here. 1 By every shady wayside and in every ancient grove, on almost every hilltop and in the outskirts of every village, you may see, while travelling through the Hondo country, some little Shinto shrine, before which, or at either side of which, are images of seated foxes in stone. Usually there is a pair of these, facing each other. But there may be a dozen, or a score, or several hundred, in which case most of the images are very small. And in more than one of the larger towns you may see in the court of some great miya a countless host of stone foxes, of all dimensions, from toy-figures but a few inches high to the colossi whose pedestals tower above your head, all squatting around the temple in tiered ranks of thousands. Such shrines and temples, everybody knows, are dedicated to Inari the God of Rice. After having travelled much in Japan, you will find that whenever you try to recall any country-place you have visited, there will appear in some nook or corner of that remembrance a pair of green-and-grey foxes of stone, with broken noses. In my own memories of Japanese travel, these shapes have become de rigueur, as picturesque detail. In the neighbourhood of the capital and in Tokyo itself-sometimes in the cemeteries—very beautiful idealised figures of foxes may be seen, elegant as greyhounds. They have long green or grey eyes of crystal quartz or some other diaphanous substance; and they create a strong impression as mythological conceptions. But throughout the interior, fox-images are much less artistically fashioned. In Izumo, particularly, such stone-carving has a decidedly primitive appearance. There is an astonishing multiplicity and variety of fox-images in the Province of the Gods—images comical, quaint, grotesque, or monstrous, but, for the most part, very rudely chiselled. I cannot, however, declare them less interesting on that account. The work of the Tokkaido sculptor copies the conventional artistic notion of light grace and ghostliness. The rustic foxes of Izumo have no grace: they are uncouth; but they betray in countless queer ways the personal fancies of their makers. They are of many moods—whimsical, apathetic, inquisitive, saturnine, jocose, ironical; they watch and snooze and squint and wink and sneer; they wait with lurking smiles; they listen with cocked ears most stealthily, keeping their mouths open or closed. There is an amusing individuality about them all, and an air of knowing mockery about most of them, even those whose noses have been broken off. Moreover, these ancient country foxes have certain natural beauties which their modem Tokyo kindred cannot show. Time has bestowed upon them divers speckled coats of beautiful soft colours while they have been sitting on their pedestals, listening to the ebbing and flowing of the centuries and snickering weirdly at mankind. Their backs are clad with finest green velvet of old mosses; their limbs are spotted and their tails are tipped with the dead gold or the dead silver of delicate fungi. And the places they most haunt are the loveliest—high shadowy groves where the uguisu sings in green twilight, above some voiceless shrine with its lamps and its lions of stone so mossed as to seem things born of the soil—like mushrooms. I found it difficult to understand why, out of every thousand foxes, nine hundred should have broken noses. The main street of the city of Matsue might be paved from end to end with the tips of the noses of mutilated Izumo foxes. A friend answered my expression of wonder in this regard by the simple but suggestive word, "Kodomo", which means, "The children" 2. Inari the name by which the Fox-God is generally known, signifies "Load-of-Rice." But the antique name of the Deity is the August-Spirit-of-Food: he is the Uka-no-mi-tama-no-mikoto of the Kojiki. [1] In much more recent times only has he borne the name that indicates his connection with the fox-cult, Miketsu-no-Kami, or the Three-Fox-God. Indeed, the conception of the fox as a supernatural being does not seem to have been introduced into Japan before the tenth or eleventh century; and although a shrine of the deity, with statues of foxes, may be found in the court of most of the large Shinto temples, it is worthy of note that in all the vast domains of the oldest Shinto shrine in Japan—Kitzuki—you cannot find the image of a fox. And it is only in modern art—the art of Toyokuni and others—that Inari is represented as a bearded man riding a white fox. [2] Inari is not worshipped as the God of Rice only; indeed, there are many Inari just as in antique Greece there were many deities called Hermes, Zeus, Athena, Poseidon—one in the knowledge of the learned, but essentially different in the imagination of the common people. Inari has been multiplied by reason of his different attributes. For instance, Matsue has a Kamiya-San-no-Inari-San, who is the God of Coughs and Bad Colds—afflictions extremely common and remarkably severe in the Land of Izumo. He has a temple in the Kamachi at which he is worshipped under the vulgar appellation of Kaze-no-Kami and the politer one of Kamiya-San-no-Inari. And those who are cured of their coughs and colds after having prayed to him, bring to his temple offerings of tofu. At Oba, likewise, there is a particular Inari, of great fame. Fastened to the wall of his shrine is a large box full of small clay foxes. The pilgrim who has a prayer to make puts one of these little foxes in his sleeve and carries it home, He must keep it, and pay it all due honour, until such time as his petition has been granted. Then he must take it back to the temple, and restore it to the box, and, if he be able, make some small gift to the shrine. Inari is often worshipped as a healer; and still more frequently as a deity having power to give wealth. (Perhaps because all the wealth of Old Japan was reckoned in koku of rice.) Therefore his foxes are sometimes represented holding keys in their mouths. And from being the deity who gives wealth, Inari has also become in some localities the special divinity of the joro class. There is, for example, an Inari temple worth visiting in the neighbourhood of the Yoshiwara at Yokohama. It stands in the same court with a temple of Benten, and is more than usually large for a shrine of Inari. You approach it through a succession of torii one behind the other: they are of different heights, diminishing in size as they are placed nearer to the temple, and planted more and more closely in proportion to their smallness. Before each torii sit a pair of weird foxes—one to the right and one to the left. The first pair are large as greyhounds; the second two are much smaller; and the sizes of the rest lessen as the dimensions of the torii lessen. At the foot of the wooden steps of the temple there is a pair of very graceful foxes of dark grey stone, wearing pieces of red cloth about their necks. Upon the steps themselves are white wooden foxes—one at each end of each step—each successive pair being smaller than the pair below; and at the threshold of the doorway are two very little foxes, not more than three inches high, sitting on sky-blue pedestals. These have the tips of their tails gilded. Then, if you look into the temple you will see on the left something like a long low table on which are placed thousands of tiny fox-images, even smaller than those in the doorway, having only plain white tails. There is no image of Inari; indeed, I have never seen an image of Inari as yet in any Inari temple. On the altar appear the usual emblems of Shinto; and before it, just opposite the doorway, stands a sort of lantern, having glass sides and a wooden bottom studded with nail-points on which to fix votive candles. [3] And here, from time to time, if you will watch, you will probably see more than one handsome girl, with brightly painted lips and the beautiful antique attire that no maiden or wife may wear, come to the foot of the steps, toss a coin into the money-box at the door, and call out: "O-rosoku!" which means "an honourable candle." Immediately, from an inner chamber, some old man will enter the shrine-room with a lighted candle, stick it upon a nail-point in the lantern, and then retire. Such candle-offerings are always accompanied by secret prayers for good-fortune. But this Inari is worshipped by many besides members of the joro class. The pieces of coloured cloth about the necks of the foxes are also votive offerings. 3 Fox-images in Izumo seem to be more numerous than in other provinces, and they are symbols there, so far as the mass of the peasantry is concerned, of something else besides the worship of the Rice-Deity. Indeed, the old conception of the Deity of Rice-fields has been overshadowed and almost effaced among the lowest classes by a weird cult totally foreign to the spirit of pure Shinto—the Fox-cult. The worship of the retainer has almost replaced the worship of the god. Originally the Fox was sacred to Inari only as the Tortoise is still sacred to Kompira; the Deer to the Great Deity of Kasuga; the Rat to Daikoku; the Tai-fish to Ebisu; the White Serpent to Benten; or the Centipede to Bishamon, God of Battles. But in the course of centuries the Fox usurped divinity. And the stone images of him are not the only outward evidences of his cult. At the rear of almost every Inari temple you will generally find in the wall of the shrine building, one or two feet above the ground, an aperture about eight inches in diameter and perfectly circular. It is often made so as to be closed at will by a sliding plank. This circular orifice is a Fox-hole, and if you find one open, and look within, you will probably see offerings of tofu or other food which foxes are supposed to be fond of. You will also, most likely, find grains of rice scattered on some little projection of woodwork below or near the hole, or placed on the edge of the hole itself; and you may see some peasant clap his hands before the hole, utter some little prayer, and swallow a grain or two of that rice in the belief that it will either cure or prevent sickness. Now the fox for whom such a hole is made is an invisible fox, a phantom fox—the fox respectfully referred to by the peasant as O-Kitsune-San. If he ever suffers himself to become visible, his colour is said to be snowy white. According to some, there are various kinds of ghostly foxes. According to others, there are two sorts of foxes only, the Inari-fox (O-Kitsune-San) and the wild fox (kitsune). Some people again class foxes into Superior and Inferior Foxes, and allege the existence of four Superior Sorts—Byakko, Kokko, Jenko, and Reiko—all of which possess supernatural powers. Others again count only three kinds of foxes—the Field-fox, the Man-fox, and the Inari-fox. But many confound the Field-fox or wild fox with the Man-fox, and others identify the Inari-fox with the Man-fox. One cannot possibly unravel the confusion of these beliefs, especially among the peasantry. The beliefs vary, moreover, in different districts. I have only been able, after a residence of fourteen months in Izumo, where the superstition is especially strong, and marked by certain unique features, to make the following very loose summary of them: All foxes have supernatural power. There are good and bad foxes. The Inari-fox is good, and the bad foxes are afraid of the Inari-fox. The worst fox is the Ninko or Hito-kitsune (Man-fox): this is especially the fox of demoniacal possession. It is no larger than a weasel, and somewhat similar in shape, except for its tail, which is like the tail of any other fox. It is rarely seen, keeping itself invisible, except to those to whom it attaches itself. It likes to live in the houses of men, and to be nourished by them, and to the homes where it is well cared for it will bring prosperity. It will take care that the rice-fields shall never want for water, nor the cooking-pot for rice. But if offended, it will bring misfortune to the household, and ruin to the crops. The wild fox (Nogitsune) is also bad. It also sometimes takes possession of people; but it is especially a wizard, and prefers to deceive by enchantment. It has the power of assuming any shape and of making itself invisible; but the dog can always see it, so that it is extremely afraid of the dog. Moreover, while assuming another shape, if its shadow fall upon water, the water will only reflect the shadow of a fox. The peasantry kill it; but he who kills a fox incurs the risk of being bewitched by that fox's kindred, or even by the ki, or ghost of the fox. Still if one eat the flesh of a fox, he cannot be enchanted afterwards. The Nogitsune also enters houses. Most families having foxes in their houses have only the small kind, or Ninko; but occasionally both kinds will live together under the same roof. Some people say that if the Nogitsune lives a hundred years it becomes all white, and then takes rank as an Inari-fox. There are curious contradictions involved in these beliefs, and other contradictions will be found in the following pages of this sketch. To define the fox-superstition at all is difficult, not only on account of the confusion of ideas on the subject among the believers themselves, but also on account of the variety of elements out of which it has been shapen. Its origin is Chinese [4]; but in Japan it became oddly blended with the worship of a Shinto deity, and again modified and expanded by the Buddhist concepts of thaumaturgy and magic. So far as the common people are concerned, it is perhaps safe to say that they pay devotion to foxes chiefly because they fear them. The peasant still worships what he fears. 4 It is more than doubtful whether the popular notions about different classes of foxes, and about the distinction between the fox of Inari and the fox of possession, were ever much more clearly established than they are now, except in the books of old literati. Indeed, there exists a letter from Hideyoshi to the Fox-God which would seem to show that in the time of the great Taiko the Inari-fox and the demon fox were considered identical. This letter is still preserved at Nara, in the Buddhist temple called Todaiji: KYOTO, the seventeenth day of the Third Month. TO INARI DAIMYOJIN:— My Lord—I have the honour to inform you that one of the foxes under your jurisdiction has bewitched one of my servants, causing her and others a great deal of trouble. I have to request that you will make minute inquiries into the matter, and endeavour to find out the reason of your subject misbehaving in this way, and let me know the result. If it turns out that the fox has no adequate reason to give for his behaviour, you are to arrest and punish him at once. If you hesitate to take action in this matter, I shall issue orders for the destruction of every fox in the land. Any other particulars that you may wish to be informed of in reference to what has occurred, you can learn from the high-priest YOSHIDA. Apologising for the imperfections of this letter, I have the honour

to be Your obedient servant, But there certainly were some distinctions established in localities, owing to the worship of Inari by the military caste. With the samurai of Izumo, the Rice-God, for obvious reasons, was a highly popular deity; and you can still find in the garden of almost every old shizoku residence in Matsue, a small shrine of Inari Daimyojin, with little stone foxes seated before it. And in the imagination of the lower classes, all samurai families possessed foxes. But the samurai foxes inspired no fear. They were believed to be "good foxes"; and the superstition of the Ninko or Hito-kitsune does not seem to have unpleasantly affected any samurai families of Matsue during the feudal era. It is only since the military caste has been abolished, and its name, simply as a body of gentry, changed to shizoku, [6] that some families have become victims of the superstition through intermarriage with the chonin or mercantile classes, among whom the belief has always been strong. By the peasantry the Matsudaira daimyo of Izumo were supposed to be the greatest fox-possessors. One of them was believed to use foxes as messengers to Tokyo (be it observed that a fox can travel, according to popular credence, from Yokohama to London in a few hours); and there is some Matsue story about a fox having been caught in a trap [7] near Tokyo, attached to whose neck was a letter written by the prince of Izumo only the same morning. The great Inari temple of Inari in the castle grounds—O-Shiroyama-no-InariSama—with its thousands upon thousands of foxes of stone, is considered by the country people a striking proof of the devotion of the Matsudaira, not to Inari, but to foxes. At present, however, it is no longer possible to establish distinctions of genera in this ghostly zoology, where each species grows into every other. It is not even possible to disengage the ki or Soul of the Fox and the August-Spirit-of-Food from the confusion in which both have become hopelessly blended, under the name Inari by the vague conception of their peasant-worshippers. The old Shinto mythology is indeed quite explicit about the August-Spirit-of-Food, and quite silent upon the subject of foxes. But the peasantry in Izumo, like the peasantry of Catholic Europe, make mythology for themselves. If asked whether they pray to Inari as to an evil or a good deity, they will tell you that Inari is good, and that Inari-foxes are good. They will tell you of white foxes and dark foxes—of foxes to be reverenced and foxes to be killed—of the good fox which cries "kon-kon," and the evil fox which cries "kwai-kwai." But the peasant possessed by the fox cries out: "I am Inari—Tamabushi-no-Inari!"—or some other Inari. 5 Goblin foxes are peculiarly dreaded in Izumo for three evil habits attributed to them. The first is that of deceiving people by enchantment, either for revenge or pure mischief. The second is that of quartering themselves as retainers upon some family, and thereby making that family a terror to its neighbours. The third and worst is that of entering into people and taking diabolical possession of them and tormenting them into madness. This affliction is called "kitsune-tsuki." The favourite shape assumed by the goblin fox for the purpose of deluding mankind is that of a beautiful woman; much less frequently the form of a young man is taken in order to deceive some one of the other sex. Innumerable are the stories told or written about the wiles of fox-women. And a dangerous woman of that class whose art is to enslave men, and strip them of all they possess, is popularly named by a word of deadly insult—kitsune. Many declare that the fox never really assumes human shape; but that he only deceives people into the belief that he does so by a sort of magnetic power, or by spreading about them a certain magical effluvium. The fox does not always appear in the guise of a woman for evil purposes. There are several stories, and one really pretty play, about a fox who took the shape of a beautiful woman, and married a man, and bore him children—all out of gratitude for some favour received—the happiness of the family being only disturbed by some odd carnivorous propensities on the part of the offspring. Merely to achieve a diabolical purpose, the form of a woman is not always the best disguise. There are men quite insusceptible to feminine witchcraft. But the fox is never at a loss for a disguise; he can assume more forms than Proteus. Furthermore, he can make you see or hear or imagine whatever he wishes you to see, hear, or imagine. He can make you see out of Time and Space; he can recall the past and reveal the future. His power has not been destroyed by the introduction of Western ideas; for did he not, only a few years ago, cause phantom trains to run upon the Tokkaido railway, thereby greatly confounding, and terrifying the engineers of the company? But, like all goblins, he prefers to haunt solitary places. At night he is fond of making queer ghostly lights, [8] in semblance of lantern-fires, flit about dangerous places; and to protect yourself from this trick of his, it is necessary to learn that by joining your hands in a particular way, so as to leave a diamond-shaped aperture between the crossed fingers, you can extinguish the witch-fire at any distance simply by blowing through the aperture in the direction of the light and uttering a certain Buddhist formula. But it is not only at night that the fox manifests his power for mischief: at high noon he may tempt you to go where you are sure to get killed, or frighten you into going by creating some apparition or making you imagine that you feel an earthquake. Consequently the old-fashioned peasant, on seeing anything extremely queer, is slew to credit the testimony of his own eyes. The most interesting and valuable witness of the stupendous eruption of Bandai-San in 1888—which blew the huge volcano to pieces and devastated an area of twenty-seven square miles, levelling forests, turning rivers from their courses, and burying numbers of villages with all their inhabitants—was an old peasant who had watched the whole cataclysm from a neighbouring peak as unconcernedly as if he had been looking at a drama. He saw a black column of ashes and steam rise to the height of twenty thousand feet and spread out at its summit in the shape of an umbrella, blotting out the sun. Then he felt a strange rain pouring upon him, hotter than the water of a bath. Then all became black; and he felt the mountain beneath him shaking to its roots, and heard a crash of thunders that seemed like the sound of the breaking of a world. But he remained quite still until everything was over. He had made up his mind not to be afraid—deeming that all he saw and heard was delusion wrought by the witchcraft of a fox. 6 Strange is the madness of those into whom demon foxes enter. Sometimes they run naked shouting through the streets. Sometimes they lie down and froth at the mouth, and yelp as a fox yelps. And on some part of the body of the possessed a moving lump appears under the skin, which seems to have a life of its own. Prick it with a needle, and it glides instantly to another place. By no grasp can it be so tightly compressed by a strong hand that it will not slip from under the fingers. Possessed folk are also said to speak and write languages of which they were totally ignorant prior to possession. They eat only what foxes are believed to like—tofu, aburage, [9] azukimeshi, [10] etc.—and they eat a great deal, alleging that not they, but the possessing foxes, are hungry. It not infrequently happens that the victims of fox-possession are cruelly treated by their relatives—being severely burned and beaten in the hope that the fox may be thus driven away. Then the Hoin [11] or Yamabushi is sent for—the exorciser. The exorciser argues with the fox, who speaks through the mouth of the possessed. When the fox is reduced to silence by religious argument upon the wickedness of possessing people, he usually agrees to go away on condition of being supplied with plenty of tofu or other food; and the food promised must be brought immediately to that particular Inari temple of which the fox declares himself a retainer. For the possessing fox, by whomsoever sent, usually confesses himself the servant of a certain Inari though sometimes even calling himself the god. As soon as the possessed has been freed from the possessor, he falls down senseless, and remains for a long time prostrate. And it is said, also, that he who has once been possessed by a fox will never again be able to eat tofu, aburage, azukimeshi, or any of those things which foxes like. 7 It is believed that the Man-fox (Hito-kitsune) cannot be seen. But if he goes close to still water, his SHADOW can be seen in the water. Those "having foxes" are therefore supposed to avoid the vicinity of rivers and ponds. The invisible fox, as already stated, attaches himself to persons. Like a Japanese servant, he belongs to the household. But if a daughter of that household marry, the fox not only goes to that new family, following the bride, but also colonises his kind in all those families related by marriage or kinship with the husband's family. Now every fox is supposed to have a family of seventy-five—neither more, nor less than seventy-five—and all these must be fed. So that although such foxes, like ghosts, eat very little individually, it is expensive to have foxes. The fox-possessors (kitsune-mochi) must feed their foxes at regular hours; and the foxes always eat first—all the seventy-live. As soon as the family rice is cooked in the kama (a great iron cooking-pot), the kitsune-mochi taps loudly on the side of the vessel, and uncovers it. Then the foxes rise up through the floor. And although their eating is soundless to human ear and invisible to human eye, the rice slowly diminishes. Wherefore it is fearful for a poor man to have foxes. But the cost of nourishing foxes is the least evil connected with the keeping of them. Foxes have no fixed code of ethics, and have proved themselves untrustworthy servants. They may initiate and long maintain the prosperity of some family; but should some grave misfortune fall upon that family in spite of the efforts of its seventy-five invisible retainers, then these will suddenly flee away, taking all the valuables of the household along with them. And all the fine gifts that foxes bring to their masters are things which have been stolen from somebody else. It is therefore extremely immoral to keep foxes. It is also dangerous for the public peace, inasmuch as a fox, being a goblin, and devoid of human susceptibilities, will not take certain precautions. He may steal the next-door neighbour's purse by night and lay it at his own master's threshold, so that if the next-door neighbour happens to get up first and see it there is sure to be a row. Another evil habit of foxes is that of making public what they hear said in private, and taking it upon themselves to create undesirable scandal. For example, a fox attached to the family of Kobayashi-San hears his master complain about his neighbour Nakayama-San, whom he secretly dislikes. Therewith the zealous retainer runs to the house of Nakayama-San, and enters into his body, and torments him grievously, saying: "I am the retainer of Kobayashi-San to whom you did such-and-such a wrong; and until such time as he command me to depart, I shall continue to torment you." And last, but worst of all the risks of possessing foxes, is the danger that they may become wroth with some member of the family. Certainly a fox may be a good friend, and make rich the home in which he is domiciled. But as he is not human, and as his motives and feelings are not those of men, but of goblins, it is difficult to avoid incurring his displeasure. At the most unexpected moment he may take offence without any cause knowingly having been given, and there is no saying what the consequences may be. For the fox possesses Instinctive Infinite Vision— and the Ten-Ni-Tsun, or All-Hearing Ear—and the Ta-Shin-Tsun, which is the Knowledge of the Most Secret Thoughts of Others—and Shiyuku-Mei-Tsun, which is the Knowledge of the Past—and Zhin-Kiyan-Tsun, which means the Knowledge of the Universal Present—and also the Powers of Transformation and of Transmutation. [12] So that even without including his special powers of bewitchment, he is by nature a being almost omnipotent for evil. 8 For all these reasons, and. doubtless many more, people believed to have foxes are shunned. Intermarriage with a fox-possessing family is out of the question; and many a beautiful and accomplished girl in Izumo cannot secure a husband because of the popular belief that her family harbours foxes. As a rule, Izumo girls do not like to marry out of their own province; but the daughters of a kitsune-mochi must either marry into the family of another kitsune-mochi, or find a husband far away from the Province of the Gods. Rich fox-possessing families have not overmuch difficulty in disposing of their daughters by one of the means above indicated; but many a fine sweet girl of the poorer kitsune-mochi is condemned by superstition to remain unwedded. It is not because there are none to love her and desirous of marrying her—young men who have passed through public schools and who do not believe in foxes. It is because popular superstition cannot be yet safely defied in country districts except by the wealthy. The consequences of such defiance would have to be borne, not merely by the husband, but by his whole family, and by all other families related thereunto. Which are consequences to be thought about! Among men believed to have foxes there are some who know how to turn the superstition to good account. The country-folk, as a general rule, are afraid of giving offence to a kitsune-mochi, lest he should send some of his invisible servants to take possession of them. Accordingly, certain kitsune-mochi have obtained great ascendancy over the communities in which they live. In the town of Yonago, for example, there is a certain prosperous chonin whose will is almost law, and whose opinions are never opposed. He is practically the ruler of the place, and in a fair way of becoming a very wealthy man. All because he is thought to have foxes. Wrestlers, as a class, boast of their immunity from fox-possession, and care neither for kitsune-mochi nor for their spectral friends. Very strong men are believed to be proof against all such goblinry. Foxes are said to be afraid of them, and instances are cited of a possessing fox declaring: "I wished to enter into your brother, but he was too strong for me; so I have entered into you, as I am resolved to be revenged upon some one of your family." 9 Now the belief in foxes does not affect persons only: it affects property. It affects the value of real estate in Izumo to the amount of hundreds of thousands. The land of a family supposed to have foxes cannot be sold at a fair price. People are afraid to buy it; for it is believed the foxes may ruin the new proprietor. The difficulty of obtaining a purchaser is most great in the case of land terraced for rice-fields, in the mountain districts. The prime necessity of such agriculture is irrigation— irrigation by a hundred ingenious devices, always in the face of difficulties. There are seasons when water becomes terribly scarce, and when the peasants will even fight for water. It is feared that on lands haunted by foxes, the foxes may turn the water away from one field into another, or, for spite, make holes in the dikes and so destroy the crop. There are not wanting shrewd men to take advantage of this queer belief. One gentleman of Matsue, a good agriculturist of the modern school, speculated in the fox-terror fifteen years ago, and purchased a vast tract of land in eastern Izumo which no one else would bid for. That land has sextupled in value, besides yielding generously under his system of cultivation; and by selling it now he could realise an immense fortune. His success, and the fact of his having been an official of the government, broke the spell: it is no longer believed that his farms are fox-haunted. But success alone could not have freed the soil from the curse of the superstition. The power of the farmer to banish the foxes was due to his official character. With the peasantry, the word "Government" is talismanic. Indeed, the richest and the most successful farmer of Izumo, worth more than a hundred thousand yen—Wakuri-San of Chinomiya in Kandegori—is almost universally believed by the peasantry to be a kitsune-mochi. They tell curious stories about him. Some say that when a very poor man he found in the woods one day a little white fox-cub, and took it home, and petted it, and gave it plenty of tofu, azukimeshi, and aburage—three sorts of food which foxes love—and that from that day prosperity came to him. Others say that in his house there is a special zashiki, or guest-room for foxes; and that there, once in each month, a great banquet is given to hundreds of Hito-kitsune. But Chinomiya-no-Wakuri, as they call him, canaffordto laugh at all these tales. He is a refined man, highly respected in cultivated circles where superstition never enters 10 When a Ninko comes to your house at night and knocks, there is a peculiar muffled sound about the knocking by which you can tell that the visitor is a fox—if you have experienced ears. For a fox knocks at doors with its tail. If you open, then you will see a man, or perhaps a beautiful girl, who will talk to you only in fragments of words, but nevertheless in such a way that you can perfectly well understand. A fox cannot pronounce a whole word, but a part only—as "Nish . . . Sa. . ." for "Nishida-San"; "degoz . . ." for "degozarimasu, or "uch . . . de . .?" for "uchi desuka?" Then, if you are a friend of foxes, the visitor will present you with a little gift of some sort, and at once vanish away into the darkness. Whatever the gift may be, it will seem much larger that night than in the morning. Only a part of a fox-gift is real. A Matsue shizoku, going home one night by way of the street called Horomachi, saw a fox running for its life pursued by dogs. He beat the dogs off with his umbrella, thus giving the fox a chance to escape. On the following evening he heard some one knock at his door, and on opening the to saw a very pretty girl standing there, who said to him: "Last night I should have died but for your august kindness. I know not how to thank you enough: this is only a pitiable little present. And she laid a small bundle at his feet and went away. He opened the bundle and found two beautiful ducks and two pieces of silver money—those long, heavy, leaf-shaped pieces of money—each worth ten or twelve dollars— such as are now eagerly sought for by collectors of antique things. After a little while, one of the coins changed before his eyes into a piece of grass; the other was always good. Sugitean-San, a physician of Matsue, was called one evening to attend a case of confinement at a house some distance from the city, on the hill called Shiragayama. He was guided by a servant carrying a paper lantern painted with an aristocratic crest. [13] He entered into a magnificent house, where he was received with superb samurai courtesy. The mother was safely delivered of a fine boy. The family treated the physician to an excellent dinner, entertained him elegantly, and sent him home, loaded with presents and money. Next day he went, according to Japanese etiquette, to return thanks to his hosts. He could not find the house: there was, in fact, nothing on Shiragayama except forest. Returning home, he examined again the gold which had been paid to him. All was good except one piece, which had changed into grass. 11 Curious advantages have been taken of the superstitions relating to the Fox-God. In Matsue, several years ago, there was a tofuya which enjoyed an unusually large patronage. A tofuya is a shop where tofu is sold—a curd prepared from beans, and much resembling good custard in appearance. Of all eatable things, foxes are most fond of tofu and of soba, which is a preparation of buckwheat. There is even a legend that a fox, in the semblance of an elegantly attired man, once visited Nogi-no-Kuriharaya, a popular sobaya on the lake shore, and ate much soba. But after the guest was gone, the money he had paid changed into wooden shavings. The proprietor of the tofuya had a different experience. A man in wretched attire used to come to his shop every evening to buy a cho of tofu, which he devoured on the spot with the haste of one long famished. Every evening for weeks he came, and never spoke; but the landlord saw one evening the tip of a bushy white tail protruding from beneath the stranger's rags. The sight aroused strange surmises and weird hopes. From that night he began to treat the mysterious visitor with obsequious kindness. But another month passed before the latter spoke. Then what he said was about as follows: "Though I seem to you a man, I am not a man; and I took upon myself human form only for the purpose of visiting you. I come from Taka-machi, where my temple is, at which you often visit. And being desirous to reward your piety and goodness of heart, I have come to-night to save you from a great danger. For by the power which I possess I know that tomorrow this street will burn, and all the houses in it shall be utterly destroyed except yours. To save it I am going to make a charm. But in order that I may do this, you must open your go-down (kura) that I may enter, and allow no one to watch me; for should living eye look upon me there, the charm will not avail." The shopkeeper, with fervent words of gratitude, opened his storehouse, and reverently admitted the seeming Inari and gave orders that none of his household or servants should keep watch. And these orders were so well obeyed that all the stores within the storehouse, and all the valuables of the family, were removed without hindrance during the night. Next day the kura was found to be empty. And there was no fire. There is also a well-authenticated story about another wealthy shopkeeper of Matsue who easily became the prey of another pretended Inari This Inari told him that whatever sum of money he should leave at a certain miya by night, he would find it doubled in the morning—as the reward of his lifelong piety. The shopkeeper carried several small sums to the miya, and found them doubled within twelve hours. Then he deposited larger sums, which were similarly multiplied; he even risked some hundreds of dollars, which were duplicated. Finally he took all his money out of the bank and placed it one evening within the shrine of the god—and never saw it again. 12 Vast is the literature of the subject of foxes—ghostly foxes. Some of it is old as the eleventh century. In the ancient romances and the modern cheap novel, in historical traditions and in popular fairy-tales, foxes perform wonderful parts. There are very beautiful and very sad and very terrible stories about foxes. There are legends of foxes discussed by great scholars, and legends of foxes known to every child in Japan— such as the history of Tamamonomae, the beautiful favourite of the Emperor Toba—Tamamonomae, whose name has passed into a proverb, and who proved at last to be only a demon fox with Nine Tails and Fur of Gold. But the most interesting part of fox-literature belongs to the Japanese stage, where the popular beliefs are often most humorously reflected—as in the following excerpts from the comedy of Hiza-Kuruge, written by one Jippensha Ikku: [Kidahachi and Iyaji are travelling from Yedo to Osaka. When within a short distance of Akasaka, Kidahachi hastens on in advance to secure good accommodations at the best inn. Iyaji, travelling along leisurely, stops a little while at a small wayside refreshment-house kept by an old woman] OLD WOMAN.—Please take some tea, sir. [After having paid for his refreshments, lyaji proceeds on his way. The night is very dark, and he feels quite nervous on account of what the old woman has told him. After having walked a considerable distance, he suddenly hears a fox yelping—kon-kon. Feeling still more afraid, he shouts at the top of his voice:-] IYAJI.—Come near me, and I will kill you! [Meanwhile Kidahachi, who has also been frightened by the old woman's stories, and has therefore determined to wait for lyaji, is saying to himself in the dark: "If I do not wait for him, we shall certainly be deluded." Suddenly he hears lyaji's voice, and cries out to him:-] KIDAHACHI.—O lyaji-San! [By this time they have almost reached Akasaka, and lyaji, seeing a dog, calls the animal, and drags Kidahachi close to it; for a dog is believed to be able to detect a fox through any disguise. But the dog takes no notice of Kidahachi. lyaji therefore unties him, and apologises; and they both laugh at their previous fears.] 13 But there are some very pleasing forms of the Fox-God. For example, there stands in a very obscure street of Matsue—one of those streets no stranger is likely to enter unless he loses his way—a temple called Jigyoba-no-Inari, [16] and also Kodomo-no-Inari, or "the Children's Inari." It is very small, but very famous; and it has been recently presented with a pair of new stone foxes, very large, which have gilded teeth and a peculiarly playful expression of countenance. These sit one on each side of the gate: the Male grinning with open jaws, the Female demure, with mouth closed. [17] In the court you will find many ancient little foxes with noses, heads, or tails broken, two great Karashishi before which straw sandals (waraji) have been suspended as votive offerings by somebody with sore feet who has prayed to the Karashishi-Sama that they will heal his affliction, and a shrine of Kojin, occupied by the corpses of many children's dolls. [18] The grated doors of the shrine of Jigyoba-no-Inari, like those of the shrine of Yaegaki, are white with the multitude of little papers tied to them, which papers signify prayers. But the prayers are special and curious. To right and to left of the doors, and also above them, odd little votive pictures are pasted upon the walls, mostly representing children in bath-tubs, or children getting their heads shaved. There are also one or two representing children at play. Now the interpretation of these signs and wonders is as follows: Doubtless you know that Japanese children, as well as Japanese adults, must take a hot bath every day; also that it is the custom to shave the heads of very small boys and girls. But in spite of hereditary patience and strong ancestral tendency to follow ancient custom, young children find both the razor and the hot bath difficult to endure, with their delicate skins. For the Japanese hot bath is very hot (not less than 110 degs F., as a general rule), and even the adult foreigner must learn slowly to bear it, and to appreciate its hygienic value. Also, the Japanese razor is a much less perfect instrument than ours, and is used without any lather, and is apt to hurt a little unless used by the most skilful hands. And finally, Japanese parents are not tyrannical with their children: they pet and coax, very rarely compel or terrify. So that it is quite a dilemma for them when the baby revolts against the bath or mutinies against the razor. The parents of the child who refuses to be shaved or bathed have recourse to Jigyoba-no-Inati. The god is besought to send one of his retainers to amuse the child, and reconcile it to the new order of things, and render it both docile and happy. Also if a child is naughty, or falls sick, this Inari is appealed to. If the prayer be granted, some small present is made to the temple—sometimes a votive picture, such as those pasted by the door, representing the successful result of the petition. To judge by the number of such pictures, and by the prosperity of the temple, the Kodomo-no-Inani would seem to deserve his popularity. Even during the few minutes I passed in his court I saw three young mothers, with infants at their backs, come to the shrine and pray and make offerings. I noticed that one of the children—remarkably pretty—had never been shaved at all. This was evidently a very obstinate case. While returning from my visit to the Jigyoba Inani, my Japanese servant, who had guided me there, told me this story: The son of his next-door neighbour, a boy of seven, went out to play one morning, and disappeared for two days. The parents were not at first uneasy, supposing that the child had gone to the house of a relative, where he was accustomed to pass a day or two from time to time. But on the evening of the second day it was learned that the child had not been at the house in question. Search was at once made; but neither search nor inquiry availed. Late at night, however, a knock was heard at the door of the boy's dwelling, and the mother, hurrying out, found her truant fast asleep on the ground. She could not discover who had knocked. The boy, upon being awakened, laughed, and said that on the morning of his disappearance he had met a lad of about his own age, with very pretty eyes, who had coaxed him away to the woods, where they had played together all day and night and the next day at very curious funny games. But at last he got sleepy, and his comrade took him home. He was not hungry. The comrade promised "to come to-morrow." But the mysterious comrade never came; and no boy of the description given lived in the neighbourhood. The inference was that the comrade was a fox who wanted to have a little fun. The subject of the fun mourned long in vain for his merry companion. 14 Some thirty years ago there lived in Matsue an ex-wrestler named Tobikawa, who was a relentless enemy of foxes and used to hunt and kill them. He was popularly believed to enjoy immunity from bewitchment because of his immense strength; but there were some old folks who predicted that he would not die a natural death. This prediction was fulfilled: Tobikawa died in a very curious manner. He was excessively fond of practical jokes. One day he disguised himself as a Tengu, or sacred goblin, with wings and claws and long nose, and ascended a lofty tree in a sacred grove near Rakusan, whither, after a little while, the innocent peasants thronged to worship him with offerings. While diverting himself with this spectacle, and trying to play his part by springing nimbly from one branch to another, he missed his footing and broke his neck in the fall. 15 But these strange beliefs are swiftly passing away. Year by year more shrines of Inari crumble down, never to be rebuilt. Year by year the statuaries make fewer images of foxes. Year by year fewer victims of fox-possession are taken to the hospitals to be treated according to the best scientific methods by Japanese physicians who speak German. The cause is not to be found in the decadence of the old faiths: a superstition outlives a religion. Much less is it to be sought for in the efforts of proselytising missionaries from the West—most of whom profess an earnest belief in devils. It is purely educational. The omnipotent enemy of superstition is the public school, where the teaching of modern science is unclogged by sectarianism or prejudice; where the children of the poorest may learn the wisdom of the Occident; where there is not a boy or a girl of fourteen ignorant of the great names of Tyndall, of Darwin, of Huxley, of Herbert Spencer. The little hands that break the Fox-god's nose in mischievous play can also write essays upon the evolution of plants and about the geology of Izumo. There is no place for ghostly foxes in the beautiful nature-world revealed by new studies to the new generation The omnipotent exorciser and reformer is the Kodomo. Notes for Chapter Fifteen1 Toyo-uke-bime-no-Kami, or Uka-no-mi-tana ('who has also eight other names), is a female divinity, according to the Kojiki and its commentators. Moreover, the greatest of all Shinto scholars, Hirata, as cited by Satow, says there is really no such god as Inari-San at all— that the very name is an error. But the common people have created the God Inari: therefore he must be presumed to exist—if only for folklorists; and I speak of him as a male deity because I see him so represented in pictures and carvings. As to his mythological existence, his great and wealthy temple at Kyoto is impressive testimony. 2 The white fox is a favourite subject with Japanese artists. Some very beautiful kakemono representing white foxes were on display at the Tokyo exhibition of 1890. Phosphorescent foxes often appear in the old coloured prints, now so rare and precious, made by artists whose names have become world-famous. Occasionally foxes are represented wandering about at night, with lambent tongues of dim fire—kitsune-bi—above their heads. The end of the fox's tail, both in sculpture and drawing, is ordinarily decorated with the symbolic jewel (tama) of old Buddhist art. I have in my possession one kakemono representing a white fox with a luminous jewel in its tail. I purchased it at the Matsue temple of Inari—"O-Shiroyama-no-Inari-Sama." The art of the kakemono is clumsy; but the conception possesses curious interest. 3 The Japanese candle has a large hollow paper wick. It is usually placed upon an iron point which enters into the orifice of the wick at the flat end. 4 See Professor Chamberlain's Things Japanese, under the title "Demoniacal Possession." 5 Translated by Walter Dening. 6 The word shizoku is simply the Chinese for samurai. But the term now means little more than "gentleman" in England. 7 The fox-messenger travels unseen. But if caught in a trap, or injured, his magic fails him, and he becomes visible. 8 The Will-o'-the-Wisp is called Kitsune-bi, or "fox-fire." 9 "Aburage" is a name given to fried bean-curds or tofu. 10 Azukimeshi is a preparation of red beans boiled with rice. 11 The Hoin or Yamabushi was a Buddhist exorciser, usually a priest. Strictly speaking, the Hoin was a Yamabushi of higher rank. The Yamabushi used to practise divination as well as exorcism. They were forbidden to exercise these professions by the present government; and most of the little temples formerly occupied by them have disappeared or fallen into ruin. But among the peasantry Buddhist exorcisers are still called to attend cases of fox-possession, and while acting as exorcisers are still spoken of as Yamabushi. 12 A most curious paper on the subject of Ten-gan, or Infinite Vision— being the translation of a Buddhist sermon by the priest Sata Kaiseki— appeared in vol. vii. of the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, from the pen of Mr. J. M. James. It contains an interesting consideration of the supernatural powers of the Fox. 13 All the portable lanterns used to light the way upon dark nights bear a mon or crest of the owner. 14 Cakes made of rice flour and often sweetened with sugar. 15 It is believed that foxes amuse themselves by causing people to eat horse-dung in the belief that they are eating mochi, or to enter a cesspool in the belief they are taking a bath. 16 In Jigyobamachi, a name signifying "earthwork-street." It stands upon land reclaimed from swamp. 17 This seems to be the immemorial artistic law for the demeanour of all symbolic guardians of holy places, such as the Karashishi, and the Ascending and Descending Dragons carved upon panels, or pillars. At Kumano temple even the Suijin, or warrior-guardians, who frown behind the gratings of the chambers of the great gateway, are thus represented—one with mouth open, the other with closed lips. On inquiring about the origin of this distinction between the two symbolic figures, I was told by a young Buddhist scholar that the male figure in such representations is supposed to be pronouncing the sound "A," and the figure with closed lips the sound of nasal "N "-corresponding to the Alpha and Omega of the Greek alphabet, and also emblematic of the Beginning and the End. In the Lotos of the Good Law, Buddha so reveals himself, as the cosmic Alpha and Omega, and the Father of the World,—like Krishna in the Bhagavad-Gita. Issendai's note: Nowadays, these figures are sometimes called "Ah" and "Un," both of which are casual ways of saying "Yes." 18 There is one exception to the general custom of giving the dolls of dead children, or the wrecks of dolls, to Kojin. Those images of the God of Calligraphy and Scholarship which are always presented as gifts to boys on the Boys' Festival are given, when broken, to Tenjin himself, not to Kojin; at least such is the custom in Matsue. This story appears in Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, by Lafcadio Hearn. It and its illustrations are available thanks to the efforts of Project Gutenberg, whose license states: This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net. |